I profiled 80 companies for Indie Hackers. Here’s what I learned.

Each company is unique, but there are common strategies and tactics that many bootstrapped have used to succeed. These are the 10 most important ones.

Like many, I was sad to see that the Indie Hackers podcast was ending. However, it turns out that Courtland and Channing are just shifting focus to written content. As part of that, they hired a team of writers, including me. I worked on the Ideas Reports, which is a big database of profiles of companies, almost all of them bootstrapped. The Ideas Reports are intended to help you get inspiration for your own projects:

I profiled 80 companies, which not only helped pay the bills as we grow Arno, but also taught me a ton about the strategies and tactics that bootstrapped companies have used to become successful. In this post, I’ll summarize what I learned.

#1) Solve your own problems.

This one was so common that it was a challenge to find new ways to describe it in each report: “scratch your own itch,” “build for yourself,” “fix what you know,” etc.

Often, the initial solution wasn’t even software and the founder wasn’t even thinking about making a company when they created it. They were just trying to make their lives a little easier. For example, Jen Yip of Lunch Money created a spreadsheet to track her expenses. It wasn’t until her sisters-in-law started using it that she realized she could turn it into a bonafide product.

A mistake that I’ve made a lot — and I think many other founders have made too — is not focusing enough on the problem. The more deeply you understand the problem you are trying to solve and who is experiencing it, the easier everything becomes because you know how to market the product and what features you need and don’t need. Experiencing the problem yourself is the fastest way to get that deep knowledge.

However, a savvy thing that many founders did was to validate that their problems were shared by others. Perhaps your problem is just a result of your own quirky workflow or preferences unique to you. With Makoto’s and my first startup, we assumed that if we built something our financial analyst co-founders loved, other analysts would love it too. It turns out that our co-founders built financial models in a way unique not just to their company but to their specific office. We had an amazing product, for a market of about 5 people, which meant that the business failed.

#2) Find a niche.

Have you ever wondered how there can be so many CRMs or product analytics tools? The answer is that within these categories, there are many niches. For example, Aleem Mawani of Streak built a CRM that is integrated deeply with Gmail, which makes it easy to update data in the CRM as you are doing emails. That one differentiating feature was enough to capture a sliver of the market and now Streak is doing $10m ARR.

In fact — and this is a point Courtland always liked to make in the Indie Hackers podcast — the existence of huge companies like Salesforce proves that there is a large market for something like a CRM. In contrast, if you are trying to build something in a new category, there is a lot more uncertainty about whether people even want that kind of product at all.

Many of the companies I profiled found specific, neglected segments of an existing market. In order to serve a ton of customers, companies like Salesforce have to compromise the user experience for some users for the sake of everyone else. The result is that dominant tools like Salesforce are good enough for a lot of people but perfect for very few. Building the perfect product for a small niche of users is a common way to build a successful indie company.

There were also a number of companies that started out broad but then niched down later. Aiming to build a product that serves everyone is a classic startup mistake. On the face of it, it makes sense: The more people that use your product, the more money you can make, right? The big problem is that it becomes really hard to market it. Who do you target? Even if you get customers, you end up with a mixed bag of users, each with different ways of using the product, which complicates product development.

This is what happened to Nick Swan at SEOTesting.com. The product was previously called Sanity Check, and it was a platform that helped you analyze your SEO data. After revenue began to stall, Nick decided to take a step back and evaluate the business. He learned that customers put Sanity Check in the same bucket as tools like Ahrefs and Semrush, which shocked him because in his mind, Sanity Check was categorically different. He came to see that his best customers used Sanity Check to analyze their SEO experiments. He rebranded, which required virtually no changes to the product itself, and within a year, growth had picked up again. By niching down, it got a lot easier for Nick to communicate what SEOTesting.com is all about (it was right there in the company name!), which meant it was much easier to acquire users.

A useful rule of thumb when thinking about marketing is that someone should read your landing page’s H1 and say, “This was built for me.” In the words of April Dunford, your product needs to be “obviously awesome” to a specific segment of users. This is especially true the younger your company is. Companies like Notion can afford the luxury of vague marketing copy, because so many people already know who they are. (However, they also have tons of marketing that is still tailored to specific user personas.)

As a bootstrapped founder, if you can’t come up with a concise, crisp H1, then this is a sign that you haven’t found your niche.

#3) Harness word-of-mouth growth.

Every single company I researched grew through word-of-mouth. The shrewdest companies understood its importance and harnessed it, which meant providing an incredible experience to their users. They strived to make the product the best it could be, but they also provided great support. I was stunned by how much time founders spent on support, even once the company was generating significant amounts of revenue. Going out of your way to help customers doesn’t scale, but it allows you to learn so much about your users, which is why “doing things that don’t scale” is one of Paul Graham’s most famous pieces of advice.

Many of the companies I profiled also gave away a lot of value for free. Some companies had a freemium model, but many more intentionally did not, the main reason being that it would result in too much support work so they wouldn’t be able to provide a great experience to those free users. Rather, companies would do things like publish a lot of useful content that ranks well for SEO. Some also created free tools. By providing value for free, this meant that a lot more people could learn about them, trust them, and then tell other people about them.

Having a generous free tier has been one of the best decisions we’ve made at Arno. Half of our users come through word-of-mouth, which is especially great because our users speak so many different languages, so it would be very challenging to reach them with other kinds of marketing. Also, it simply feels good to be able to help students who don’t have a lot of money.

#4) If you build it, they will not come.

Among the 80 companies I profiled, there was only one that did no marketing in order to reach a decent scale: Going (formerly Scott Cheap’s Flights). Scott simply started sending out his email newsletter to friends and family and from there it went viral. Every other company had to grind to get their users.

This grind can take different forms. For some, like Marie Martens of Tally, it meant spending pretty much all day, every day for months manually reaching out to creators. For others, it means being active on Twitter or creating a bunch of SEO content.

#5) The “Big Launch” is a myth.

There seems to be this belief that if you get Product of the Day on Product Hunt, your company is going to succeed, and many startups put a lot of effort into having a big launch.

What happened with the companies I profiled was that even if they had a successful launch, this was a temporary spike in sign ups and subscribers, but then it subsided within a week or two. At that point, founders had to do the hard work of building out durable acquisition channels and improving the product in order to convert customers and keep them from churning. This is what happened to Michele and Mathias Hansen of Geocodio. Despite being at the top of Hacker News for a whole day, they only made $31 in their first month.

I’ve learned that a successful launch is good validation of your idea, but it doesn’t mean that you have reached zero gravity and that the momentum from the launch will carry you indefinitely.

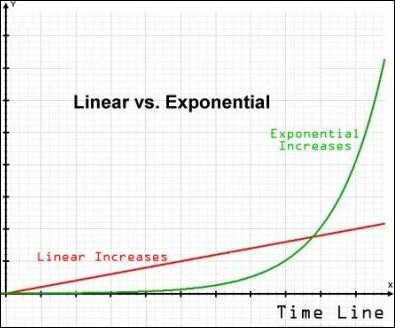

#6) Startups grow exponentially.

All the companies I profiled followed exponential growth curves (the green line) as opposed to linear growth curves (the red line).

This meant that typically for several years, their growth was slow, perhaps even non-existent some months — look at how long that green line is basically at 0! But they kept plugging away, and eventually growth started to take off. For Lane Wagner of Boot.dev, the growth in the early days was so painfully slow that he even tried to sell the company. It’s now pulling in over $100,000 per month.

For some companies, the inflection point is sharp. For others, it’s more gentle. In almost none of them was there a specific factor that caused the big acceleration in growth. Rather, it just seemed to be the steady accumulation of improvements across different areas of the business combined with word-of-mouth which grows at an exponential rate. (However, I plan to write a blog post in which I try to pin down why startups grow exponentially as opposed to linearly. If you have any thoughts, please send me an email: otto.nagengast [at] gmail.com 🙂)

#7) It takes years.

Seeing the growth rates and timelines of so many companies really drove the point home to me that building a successful company takes years, not weeks or months. These days, I pretend like I’m getting a PhD. It takes around 5 years to get one, become an expert in a field, and get a job that pays you decent money. That’s the timeline that I assume I’m on as a bootstrapped founder.

To underscore some advice I heard so many times on the Indie Hackers podcast: Just don’t quit. If you can stay in the game long enough, and continue improving your company a little bit each day, the experience of the 80 companies I profiled suggests that eventually, growth will accelerate.

#8) Target agencies.

Unfortunately, I didn’t find any hacks for building a successful company. But, targeting agencies is perhaps the one exception. Agencies have multiple clients. If you can sell your tool to one agency, they likely will want to use it with each of their clients. This means that just by selling to that one agency, you can end up effectively selling to tons of companies, but with none of the sales work.

Agencies are also great targets because they are eager to find ways to save time so that they can can take on more clients.

#9) You don’t have to go full-time right away.

Around half the companies I profiled were built for many years while their founders held down other work, typically freelance or consulting work but sometimes even full-time jobs. You don’t need to risk all your money and live off ramen to be a successful startup founder. You can grow it slowly as a side project. You can transition to it part-time. Once you’re making enough revenue, then you can go full-time on it.

#10) Talk to customers.

This advice has become so common that it feels almost silly to say once more. Yet, founders of company after company I profiled talked about the importance of speaking with customers and using their feedback to improve the product.

I’ve realized that the advice “talk to customers” is good but not particularly useful because it doesn’t tell you how to go about doing it. For this, The Mom Test is essential reading.

With Arno, we’ve discovered that there’s a big difference between talking to a lot of users one time and talking to the same users many times. When you have a bunch of one-off conversations, you end up covering the same ground over and over. But, if you talk to the same users repeatedly, you will learn a lot more about how they are using the product and what things they’re doing around your product. Plus, you develop a real relationship with them, which motivates me to work harder on Arno so that I can help these people who have become friends.

I’m feeling this in real time. When I switched my app from dev to prod, nothing magically changed - there was no sudden traffic spike. What’s actually moving the needle is reaching out to people one by one. It seems like that’s the only consistent early strategy. Is there any other repeatable alternative at the very start?

Interesting...

May be market size, strong demand, unique positioning, cheap marketing channel also matters a lot.

underrated post

I'm curious about a few things. Maybe you can give some insight.

What types of companies/products did you profile?

How many founders had business/sales/marketing experience going into their venture?

Regarding #6 and #7:

What was the tipping point?

Why did it take years to become successful after so long of slow growth or stagnation?

What changed around the point of accelerated growth?

My prediction is that it took years to get traction for founders who lacked previous business and sales experience. Any successful business owner/founder knows that the product is only 10% of success, the other 90% is your ability to sell it.

I think about how I will market a product and who I will make cold calls to before I even begin coding the first line. If there is not a very clear path to making 10k+/month within the first 3 months, the project gets scrapped.

A couple of tips.

1) If you are in the first years of a new business and you aren't making 100+ sales calls a day, it is absolutely going to take years, if ever, to hockey stick.

2) If you are making 100+ calls a day and you aren't making at least 20k/month by the end of the first year either your product sucks or you suck at selling. If you can't fix your bad product, scrap it and build something that doesn't suck. If you can't sell, learn how or find another calling.

3) If you can't call your customers directly on the phone (because they aren't a business) you are going to have a very hard time starting a business. There is a reason that VCs are only focusing on B2B companies and not even looking at B2C companies anymore. It's because you lose a great deal of control when you are not able to directly contact the people you are selling to. If you can't make sales calls, and you rely on google and facebook ads and how well you did on producthunt you are going to spend a lot of money and do a lot of waiting. If you can't make sales calls, you are not able to be proactive, you just have to sit and wait and hope somebody clicks on your ads.

4) If you are a business owner/founder, your main job is as the lead salesperson. If you don't know how to sell, you need to learn. If you don't want to learn how to sell, don't start a business.

Lots of interesting thoughts here.

What types of companies/products did you profile? => I focused mainly on bootstrapped companies. Within that, it was primarily businesses with software. But there were companies that were pure information products or more or less agencies.

How many founders had business/sales/marketing experience going into their venture? => The majority of founders were repeat founders (or they had at least built some kind of project in the past), so they had experience with user acquisition.

What was the tipping point? Why did it take years to become successful after so long of slow growth or stagnation? What changed around the point of accelerated growth? => Like I said in the post, there was almost never one clear cause that the founders could point to. It seems that different aspects of the business started to come together. In other words, it was the steady accumulation of improvement in different areas of the business that eventually paid off.

Regarding your tips, I'm glad that you found a formula that sounds like it works for you -- but I would encourage you to broaden your view of how to build a successful business :) I agree that investors prefer B2B businesses. We have friends in YC who said that B2C businesses are actively discouraged. Sure enough, when we applied to YC with Arno, one of the partners asked if we had any other ideas, perhaps from our time building Arno. He was nudging us in the direction of B2B. We said that we didn't, and we didn't get in.

I think after finding a real problem, the most important factor for startup success is passion, at least for me. Do you actually care about the problem and the people who experience it? The path to decent revenue may be more clear in a B2B business, but, I worked at B2B companies in the past and, frankly, I never really cared about our users. But with Arno, our users are students, many of whom are under 25 and live in developing and middle income countries. We certainly could've picked a more lucrative market, but we wouldn't enjoy the work nearly as much as we do now.

If revenue is a big motivator for you, and you don't care so much about the product, then I think B2B is a better avenue. But if you're like us, and you care about the product and impact it has on the world more than the amount of money you make, then B2C may be a better fit :)

The bottom line: There is no one way to build a company. I encourage anyone reading this to create your own definition of success and figure out if and how a company helps you achieve that. That's what indie hacking is all about :)

Hey! Thanks for getting back to me about those questions. Great insight there.

However, I think you might need to broaden your understanding of what a B2B company is.

Facebook is a great example of a B2B company that is disguised as a B2C company. They have created a fun place for consumers to congregate and create posts. The customers are the companies that buy ads. Those are the real users they are targeting. Pretty big impact on the world. Also highly profitable.

I have a job board that is location specific, and it massively improves the ability for consumers to find jobs, but it is paid for by the B2B users that pay for job postings. My job board service greatly impacts the world for the people living in the area. It's also very profitable. I have almost no overhead costs.

Currently, I'm building a real estate MLS alternative. We will have monetization from both B2B and B2C customers, but we'll be able to control our trajectory because we can directly contact our B2B prospects. If it takes off, it will have a massive impact on the world while also having very high profit margins.

You might not fully understand what a B2B product is if you think that people building them believe that "revenue is a big motivator for you, and you don't care so much about the product".

Very fair points -- thank you for making them. I completely agree that there can be interesting and impactful B2B companies. That said, I stand by my statement: "If revenue is a big motivator for you, and you don't care so much about the product, then I think B2B is a better avenue."

What I was referring to specifically are those B2B companies that solve a specific business problem and that save a company time and/or help them make more money and the company pays you for it. Like I said, I worked at more "conventional" B2B companies like this in the past, and I just never found much personal meaning in helping businesses, even if I knew the people at those businesses who were benefitting from the product. If the size of the deals and revenue meant more to me, I think I would've been more motivated.

That said, perhaps this advice about B2B v. B2C is just me projecting my own feelings onto others. To each their own :)

"It's because you lose a great deal of control when you are not able to directly contact the people you are selling to. If you can't make sales calls, and you rely on google and facebook ads and how well you did on producthunt you are going to spend a lot of money and do a lot of waiting."

Would you ever consider in-person engagement a viable form of "direct contact"?

Example: You are trying to help kids learn skills outside school, or help their parents prepare them for exams/college apps. Would you consider going to school or parent gatherings, or are group events too unfocused to get true feedback?

In the event that 1-on-1 is the only truth, what about DMing people from a subreddit, Facebook community, Slack group, X, or Discord server? True, it might not start out as voice, but could you see that outreach developing into relationships that you can then call over Slack or Discord?

I am not trying to argue your point, more curious about what other forms of customer contact are sustainable for the early seed, getting the flywheel spinning. Phone calls feel very hit-or-miss because even if you can call them, it's hard to get the other person interested if they smell a salesperson. If you've tried in-person or online communities, let me know! Thanks for your insight!

Is SEO part still relevant at the age of AI search? I mean, they will just summarize key points from 2-3 sources and real humans won't even read the source itself

This is the question many people are asking. So far, AI hasn't killed our SEO at Arno, but I wouldn't be surprised if over time, our posts get less traffic as people just rely on Google's AI summaries.

However, I think those AI summaries are most useful for finding a specific fact. For example, the phone number for customer service for a specific company. But, if you want a more detailed guide or some thoughtful analysis, then I think many people would prefer to read something written by an expert.

What may end up happening is that a lot of "long tail" SEO will get eaten up by AI search because there are so many "long tail" posts that were written to answer a very specific question that someone asks for. But, I think that there will still be plenty of demand for thoughtful content written by humans.

The SEO part is really helpful, thx for sharing.

I'm stuck on the point about talking to customers. I read the Mom Test, and my main issue is I don't spend enough time in day-to-day life around enough density to ask a certain persona about their problems, or gather any sort of signal about what they might buy to solve their pain point.

Let's say you want to help high school students learn English so they can write good college essays, or solve some problem that prevents them from getting accepted. If you're not a teacher, how do you regularly access students -- or their parents? It's creepy to approach randos at the library or schoolyard. You could tutor kids, but it takes months and years to build a clientele if you haven't been a private tutor before. I may know like two or three people that have kids in the right age range, hardly enough of a sample size to make sweeping judgments even if the potential userbase is huge.

Another example: Let's say you work in a company. If your entire team was software engineers, then I could see canvassing them for good problems to solve, but what if the people around you every day do all sorts of different things, that don't fit into a niche? My own team has a product manager, a graphic designer, a typographer, a frontend engineer, a backend engineer, some translators of different languages and skill levels, and QA. They're all knowledge workers, but they don't share interests in the same things or have the same problems. Minimal overlap other than us working in the same office and toward the same final product.

What would you advise in terms of more actively immersing yourself in a certain niche or persona, so your "Mom Test" interactions are more informative and trustworthy? Did any of the consumer (B2C) companies in your survey do anything creative to harvest users out of a limited contacts list, that they could reliably canvass or test ideas on? (Thinking of things like Nikita Bier hiring school ambassadors or randomly following/friending students of a high school on Instagram for Gas App.)

For Arno, we did a lot of cold messaging just to get people on the phone. This was probably my least favorite part of the entire journey because you're just begging strangers to talk with you for 30 minutes and the response rate is like 2%. The more personal connection you share with someone, the more likely they are to get on the phone with you. For example, for a previous startup idea in the real estate space, I started reaching out to alums from my college, and the response rate was way higher.

Probably the majority of companies I profiled were started to solve the founder's own problem. Maybe they did some interviews or somehow validated that their problem wasn't unique to them, but most of them just launched something and saw if people started using it. Even if others didn't use it, they still had a useful tool for themselves. Don't underestimate how much money these small solutions can make. For example, Cory Zue built a tool that generated placecards (for example, for something like a wedding) from a list of names. That was it. He ended up making a lot of money by just solving this specific problem he had experienced in the past.

It's also much easier to get users on the phone than random strangers. So, you can start with a very narrow product, get users on the phone, and learn about how they're using the product, what other parts of their workflow are happening outside the tool, what they think your tool is missing, etc. That allows you ship more product, get more users, get more feedback, and now you have a flywheel going. This is very much what has happened with Arno.

Finally, you can start to hang out in online communities. Several of the companies I profiled got started this way. By seeing what questions people are asking, you can see where their pain points are. If you actually get active and start answering people's questions, then you can see where the solutions are lacking and where there may be gaps that you can fill.

There are tons of talented people out there who can and do build incredible products. But, they don't make any money because the product doesn't solve a real problem so no one will pay for it. I think problem discovery is one of those things that can require just a lot of that unsexy startup hustle. Fortunately, once you have a real problem, your chances of success are much higher!

I found it helpful! thanks

Thanks for sharing.

Can you profile mine? http://pentaclay.com

I help startup founders launch websites within hours with my premium Framer Website Templaes.

"#8) Target agencies" is a nice idea. Kind of like "Sell to the rich". Thanks for that! Great article :)

These insights are incredibly timely. As someone running a price comparison platform, the "Find a niche" section particularly resonated with me.

Until now, we've been trying to "compare everything!" but I'm realizing that focusing on ㅡmuch more specific categories (e.g., home/living, fashion) or specific buyer personas (e.g., price-conscious women in their 20s) might be more effective. The advice about making people think "This was built for me!" when reading your landing page H1 really hit home. Just shared this article with my team - that insight about landing page H1 needing a powerful single line really struck a chord. After reading this, I immediately proposed to our team that we need something more targeted and compelling. The article's point about being "obviously awesome" to a specific segment really drives home that we've been too broad in our messaging. As April Dunford mentioned, it needs to be immediately clear WHO we're for, not just WHAT we do.

Thanks for sharing such valuable insights! I'm curious - were there any successful cases of e-commerce price comparison platforms in your research? Would love to learn from their experiences.

Hey! Glad you found the article helpful :) You may also find this article helpful as you are trying to perfect your messaging: https://review.firstround.com/finding-language-market-fit-how-to-make-customers-feel-like-youve-read-their-minds/

I did not come across any e-commerce price comparison platforms in my research, unfortunately, so I can't be of any help there.

Great

this is so true 👉#4) If you build it, they will not come.

Great article. I agree totally with #4 and #5

I've saved this to read again sometime. Great post

This is so interesting.. thank you for sharing

Great post! I like your point about targeting agencies as they usually have multiple customers.

Solving my own problem is how I started aiselfi.es

hahah the big launch is a myth but still something we can't hope but happens!!

This is so interesting.. thank you for sharing